The Mindfulness-based Self-Efficacy Scale – Revised (MSES-R) is a 22-item self-report scale for adults and adolescents (age 16+) designed to measure levels of self-efficacy in overcoming daily stressors. The MSES-R was developed with a focus on measuring skills that people felt improved in their lives as a consequence of mindfulness practice.

It was developed to measure the confidence in achieving the original purpose of mindfulness (reducing suffering), rather than measuring the construct of mindfulness itself. This is consistent with studies that have highlighted links between mindfulness and several forms of self-efficacy for improving self-regulation (Cayoun et al., 2022).

Mindfulness based self-efficacy is assessed in six subscales:

- Emotion Regulation

- Social Skills

- Equanimity

- Distress Tolerance

- Taking Responsibility

- Interpersonal Effectiveness

The MSES-R is specifically designed as an outcome measure, where it assesses skills which typically develop from becoming more mindful while confronted by common stressors in daily life. When administered more than once the change in scores are graphed over time. A successful mindfulness based intervention is indicated by an increase in the total score.

The MSES-R is expected to be particularly helpful in a clinical context because a strong sense of self-efficacy (i.e., a person’s perception or belief in their ability to perform certain skills or act effectively to attain their goals; Bandura, 1997) is related to greater effort, persistence, and self-benefitting behaviours (Schwarzer, 2008).

Psychometric Properties

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the MSES-R scores collected online from two Australian samples (clinical N = 1378; community N = 2866), two Canadian samples (clinical N = 595; community N = 321), and one Australian university student sample (N = 521). The MSES-R provided adequate fit across all samples (Cayoun et al., 2022). The overall MSES-R measure was highly reliable (alpha = 0.89), as was the Emotion Regulation subscale (0.88). The reliability of the Social Skills subscale (0.72) was in the low to moderate range, with the reliability of the other subscales being low (0.47-0.65). Due to the low reliability of some subscales, it is recommended that users should rely on the total MSES-R score (Cayoun et al., 2022), but studies have also shown that subscale scores can be helpful in clinical settings (e.g., Francis, et al., 2022). The test-retest reliability of the MSES-R total score over two weeks was 0.88.

Higher overall scores on the MSES-R were significantly associated with higher scores on the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) overall (r = 0.62), as well as higher scores on many of its subscales (Cayoun et al., 2022). Higher scores on the MSES-R were also significantly associated with lower overall DASS scores (r = − 0.68), and on each subscale: Depression (r = − 0.60), Anxiety (r = − 0.56), and Stress (r = − 0.62; Cayoun et al., 2022).

In a validation study by Cayoun et al. (2022), 4638 adults from the general community (54% females and 46% males, mean age = 38.9) were assessed using the MSES-R. Although raw scores were provided by Cayoun et al. (2022), we have computed average scores (raw score divided by the number of questions) so that subscales can be compared. The below means and standard deviations are used to compute percentile ranks, with both the raw scores (Cayoun et al., 2022) and calculated average scores presented:

1. MSES-R Total Score: Raw Score: Mean 57.7 (SD 13.3); Average Score: Mean 2.6 (SD 0.6)

2. Emotion Regulation: Raw Score: Mean 14.8 (SD 5.4); Average Score: Mean 2.5 (SD 0.9)

3. Social Skills: Raw Score: Mean 7.97 (SD 2.6); Average Score: Mean 2.7 (SD 0.9)

4. Equanimity: Raw Score: Mean 9.96 (SD 3.1); Average Score: Mean 2.5 (SD 0.8)

5. Distress Tolerance: Raw Score: Mean 8.1 (SD 2.5); Average Score: Mean 2.7 (SD 0.8)

6. Taking Responsibility: Raw Score: Mean 7.95 (SD 2.5); Average Score: Mean 2.7 (SD 0.8)

7. Interpersonal Effectiveness: Raw Score: Mean 8.9 (SD 2.2); Average Score: Mean 3.0 (SD 0.7)

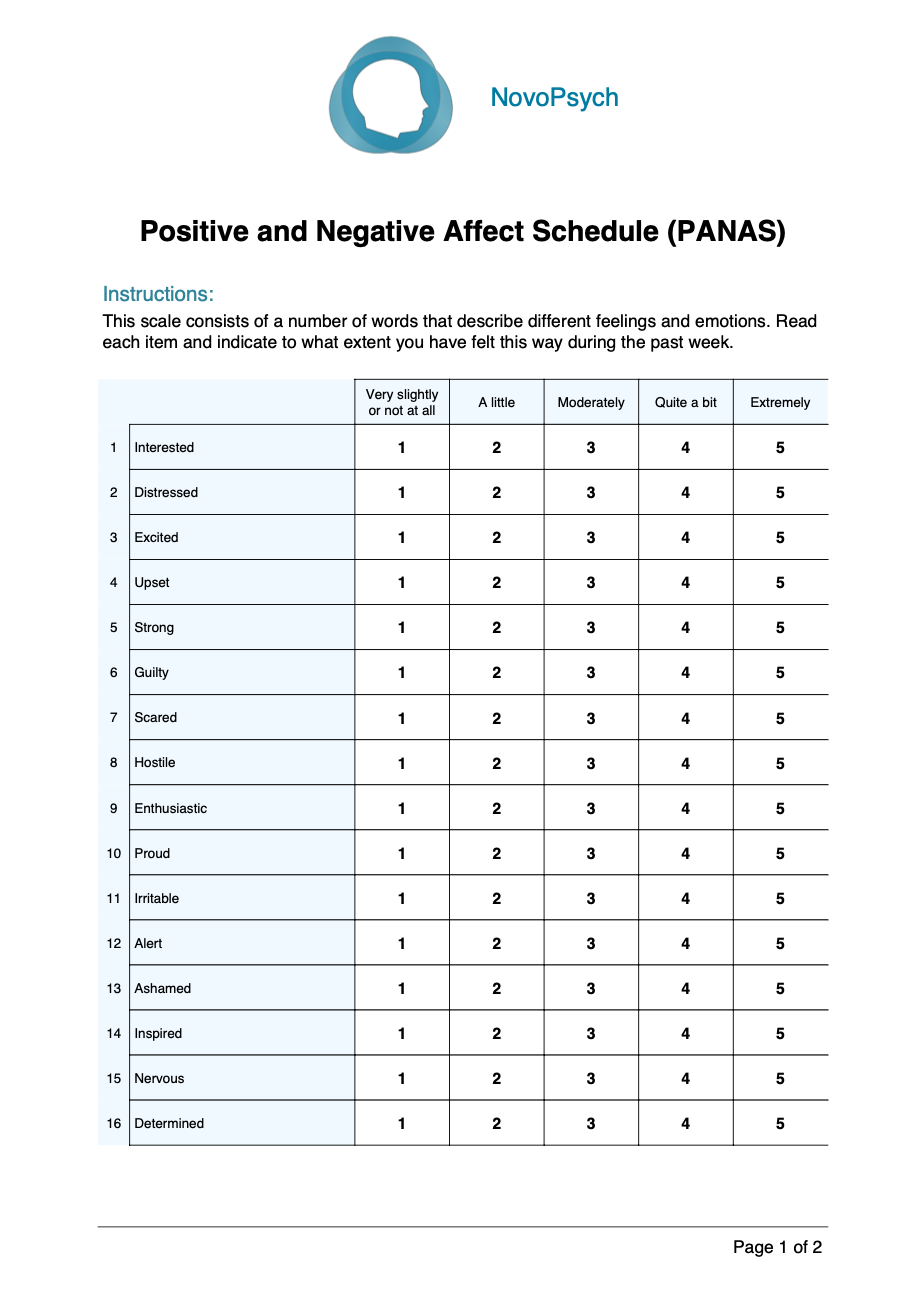

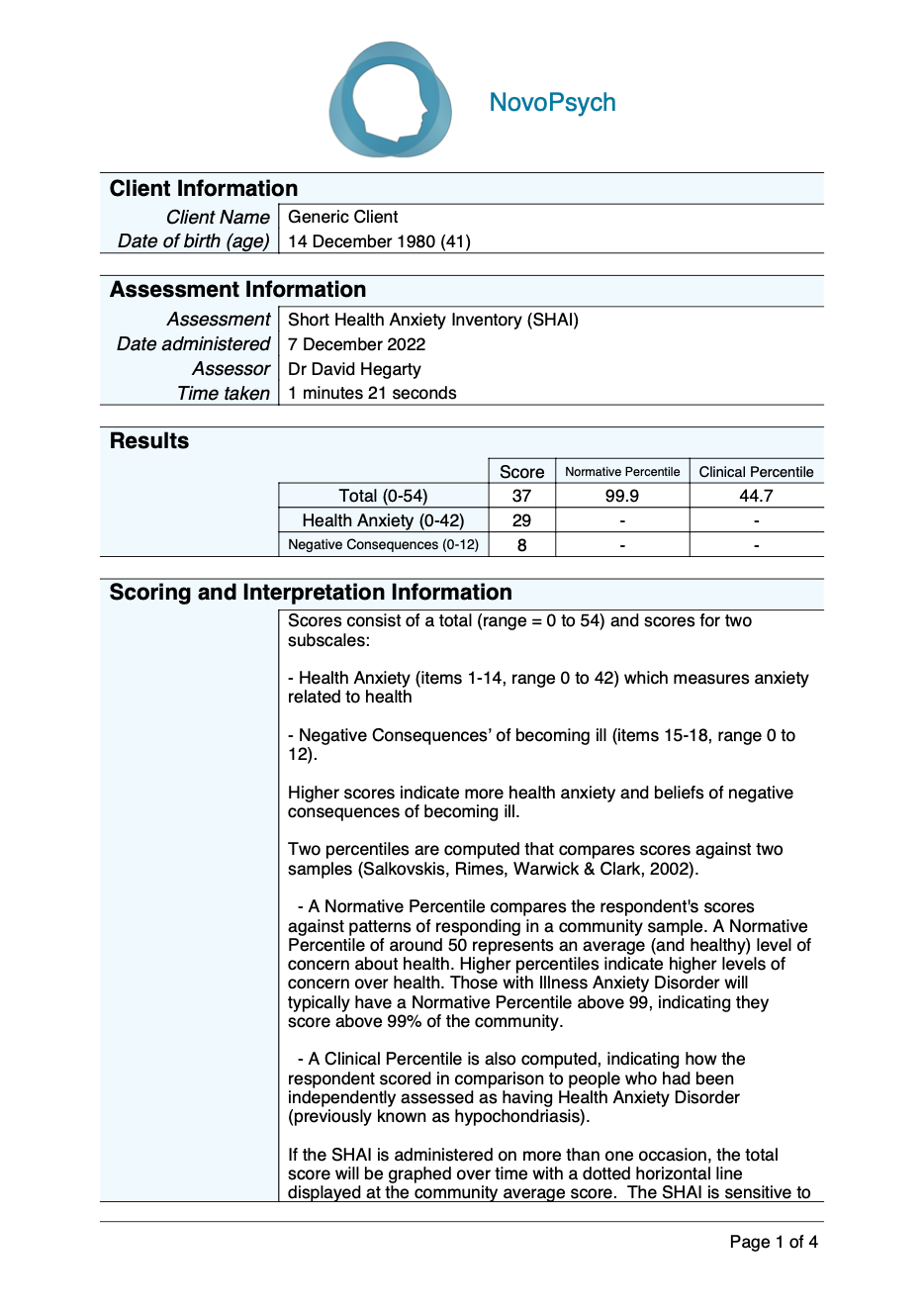

Scoring and Interpretation

Scores are presented as Average Scores with a range between 0 and 4, where higher scores are indicative of higher self-efficacy with mindfulness skills.

A normative percentile is also calculated which compares the respondents score to a community sample. A percentile rank of 50 indicates an average level of self-efficacy with mindfulness skills in comparison to the normative comparison group. Interpretation using the percentile is useful because it contextualises responses in comparison to healthy peers.

There are 6 subscales for the MSES-R:

- Emotion Regulation (items 1, 4, 6, 7, 12, 18): relates to an involuntary or subconscious emotional response that is well modulated.

- Social Skills (items 2, 3, 20): social abilities in the broader sphere of interaction.

- Equanimity (items 5, 10, 13, 19): the ability to normalise difficulties and prevent reactivity.

- Distress Tolerance (items 8, 16, 17): inhibits avoidance of experiential intolerance or discomfort.

- Taking Responsibility (items 11, 21, 22): clarity of interpersonal boundaries and locus of control.

- Interpersonal Effectiveness (items 9, 14, 15): the ability to connect with others within the intimate sphere of relationships.

Developer

Cayoun, B., Elphinstone, B., Kasselis, N., Bilsborrow, G., & Skilbeck, C. (2022). Validation and Factor Structure of the Mindfulness-Based Self Efficacy Scale-Revised. Mindfulness, 13(3), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01834-6

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Francis, S. E. B., Shawyer, F., Cayoun, B., Enticott, J., and Meadows, G. N. (2022). Group Mindfulness-integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy (MiCBT) reduces depression and anxiety and improves flourishing in a transdiagnostic primary care sample compared to treatment-as-usual: a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 815170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.815170

Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to pre-dict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 1–29. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1111/j. 1464- 0597. 2007. 00325.x